Just back from a few days at the coast, but in time for a new segment of Cline on the Constitution. In reading though some of the Supreme Court’s recent decisions, I came across an interesting issue which I’m sometimes asked about.

Universal Injunctions.

The situation is this. Congress passes a law or the President attempts to implement a new policy. An advocacy group such as the ACLU finds a client, picks a friendly federal district court and files suit. The Judge then issues an injunction stopping the implementation of the law, not just as to the person before the court, but applies it to everybody nationwide. And of late, it happens over and over virtually paralyzing the political branches of government.

Does the Constitution provide district courts with that kind of power?

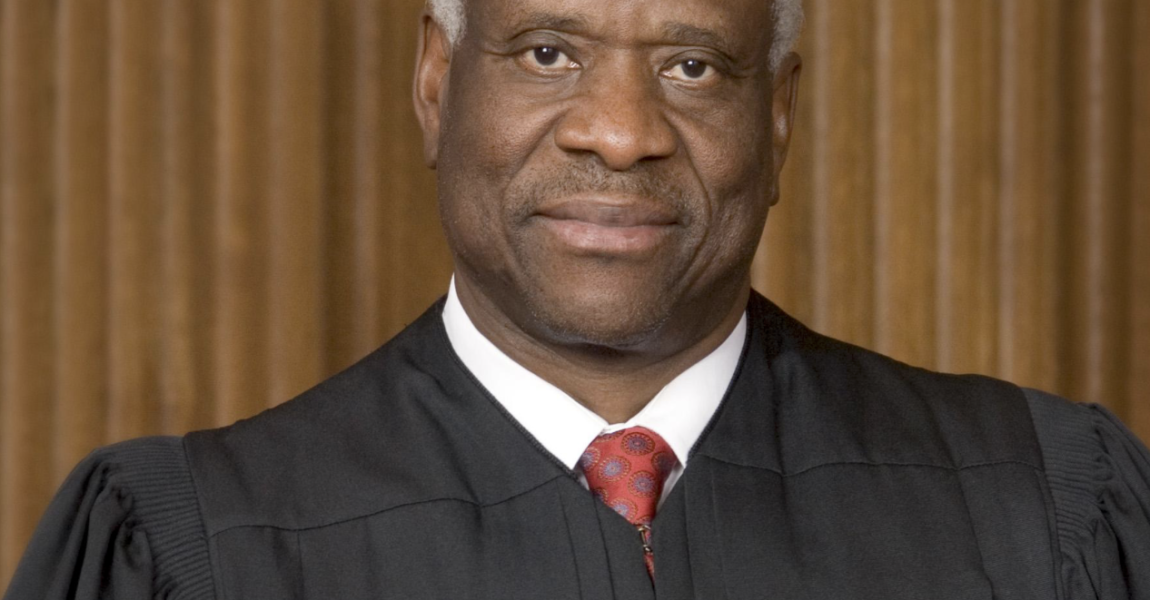

Justice Clarence Thomas has seldom received the same accolades as his brothers and sisters on the bench. But then he doesn’t seek the level of attention as some of them seem to crave and cultivate. However, he has offered many intelligent, insightful and courageous opinions, often as concurring or dissenting opinions.

In a recent opinion he took up a very important issue the federal judiciary is reluctant to address because it goes to their own power and conduct. Justice Thomas posited the question of whether local District Court Judges, who occupy the lowest rung on the Federal Judicial ladder, can constitutionally issue orders on cases before them and then apply those orders to the entire nation affecting millions of citizens and non-citizens who are not before them. And can they restrain the entire federal government from acting everywhere.

The legal procedures used to exercise such great power are called “Universal Injunctions.”

A Universal Injunction was used by a district court in Hawaii to prevent the President from implementing orders banning certain non-citizens from traveling to the United States from foreign lands. The Supreme Court overturned the actions of the Hawaii court and dissolved the injunction.

Justice Thomas in his concurring opinion in that case confronted the issue of Universal Injunctions and their constitutionality.

It is important to understand how the judicial power is being used when universal injunctions like the one found improper by the Supreme Court are used.

This is not a situation where an appellate court reviews the results of a trial in a lower court, i.e. a District Court, and rules something was done wrong in the lower court and issues an opinion. This is not a situation where a case of national import is ruled on by the Supreme Court.

This is a situation where over six hundred local lower court judges have asserted the power to take a local case and rule nationally.

First of all, there is nothing more noble or intelligent about federal judicial officers than any other occupation or profession. They have the same foibles and biases as the rest of us. Some have less. Some have more. They are largely political appointees, and too few leave their political views behind.

Yet, these six hundred individuals, when they issue Universal Injunctions, are in effect acting as an unelected, unaccountable super legislature.

Not exactly what our founders envisioned.

It is well to remember that all federal courts with the exception of the Supreme Court are creations of Congress and under the Constitution their jurisdiction is subject to restrictions and exceptions placed upon them by Congress. The constitution provides only for One Supreme Court and “such other courts as Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.” The lower federal courts were mostly established by the Judiciary Act of 1789.

Issuing a Universal Injunction is not a power expressly given to federal district court judges by the Constitution or act of Congress. It is an extraordinary power the courts must carve out of the general judicial power based upon historically recognized principles.

In his opinion, Justice Thomas examined the history of a court’s power to use extraordinary remedies such as injunctions.

He traced its history to the ancient equity courts in England. There the power was vested in the Exchequer of the Chancery to fashion remedies where the strictures of the common law could not find a way to deliver justice in unusual cases. However, the power was always severely limited, and it actually originated as an aspect of the “divine” power of the Kings. Interestedly, it could not be used to restrain the Crown because that was the source of the power.

Justice Thomas went on and reviewed the debates over extraordinary equity powers at the time of our nations’ founding. And he emphasized that In the federalist and anti-federalist papers the accepted wisdom was that there was a need for judicial restraint less the whole idea of functioning democracy be undermined.

Sounds familiar.

And finally, he noted that the use of “universal” injunctions did not debut in America until the 1960s. It first appeared in a case dealing with worker’s wages. The constitutional basis for the power was never really considered in any depth. Mainly because it was used rarely used. At least until recently.

And it does seem that the unprecedented increase in their use was concurrent with the politicization of the federal judiciary. A politicization facilitated by the judiciary’s willingness even at their lowest level to intervene in affairs traditionally the responsibility of the other co-equal branches of government and to exercise power or millions of citizens who are not parties to the cases before them.

As Justice Thomas opined:

“American court’s tradition of providing equitable relief only to parties was consistent with their view of the nature of judicial power. For most of our history, courts understood judicial power as “fundamentally the power to render judgements in individual cases.” Historically, Court’s only provided equitable relief to the parties to the suit. They never ventured outside the case they were call upon to decide which is exactly what is done when a universal injunction is issued.

It is a fundamental rule of Standing that the Constitution limits the Courts as to who can sue to vindicate certain rights. A person cannot bring suit to vindicate “public rights”, that is rights held by the community at large without showing of some specific injury to himself. And a plaintiff cannot sue to vindicate the private rights of someone else, a third party. Such claims have historically been considered beyond the authority of the courts. Otherwise the courts end up setting policy which they are not supposed to do. The framers reserved public policy question to the legislative process.

The argument in the favor of the use of universal injunctions is that they give the judiciary a powerful tool to check the Executive Branch. But the argument does not explain where the power comes from. As Justice Thomas explains,

“But these arguments do not explain how these injunctions are consistent with the historical limits on equity and judicial power. They at best “boil down to a policy judgement” about how powers ought to be allocated among our three branches of government, but the people already made that choice when they ratified the constitution.”

Justice Thomas concludes by stating “in sum, universal injunctions are legally and historically dubious. If federal courts continue to issue them, this Court is duty-bound to adjudicate their authority to do so.”

Indeed.

For other writings by Phil Cline on the Constitution, visit philcline.com