I am back with a new segment of Cline on the Constitution.

Took a little hiatus to explore the Mississippi via Paddle Boat. Great trip.

I then monitored the resumption of hearings on Justice Kavanaugh. Much has been discussed about Due Process and the Presumption of Innocence. I won’t repeat the various arguments.

But a couple of the images did stick with me. The first was of a cadre of the clueless actually clawing at the doors of the Supreme Court. I was put in the mind of an army of the undead, like a movie ready made for the approaching Halloween called “Zombies and the Law”.

The second image was of Senators ducking out of the hearing to give fiery speeches to the Mob pressing in on the steps of the Capitol.

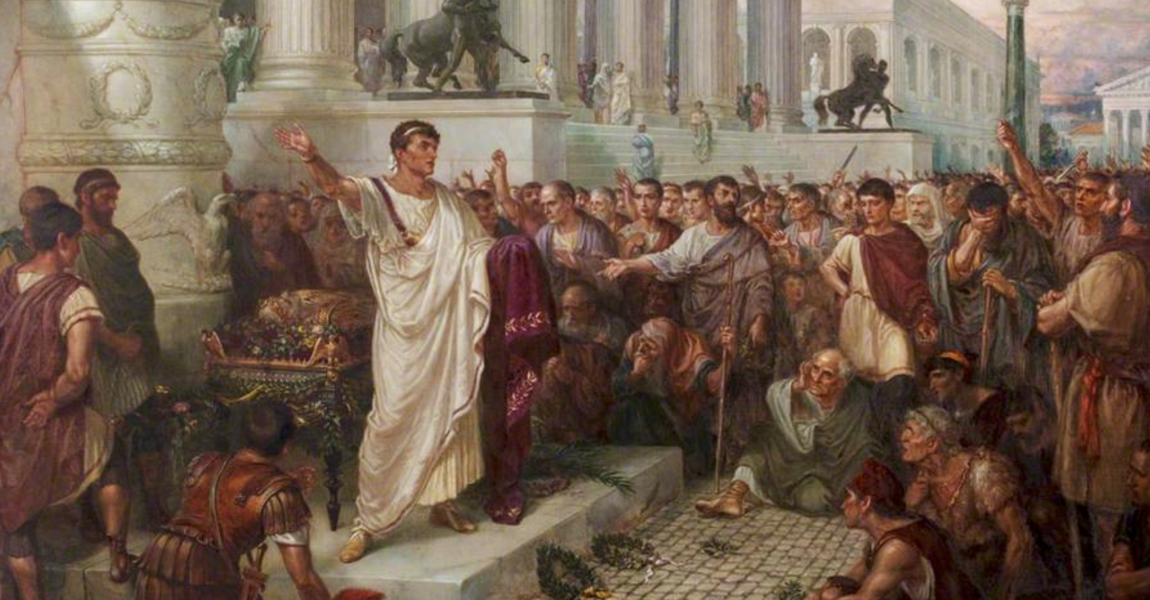

It reminded me of Brutus addressing the Mob after joining with other senators in the assassination of Caesar. These Senators rushing to the microphones after engaging in their own assassination (of character) seemed unaware of the lesson that the Mob may very well turn on them next. As they did on Brutus and the others when Anthony, in one of the most famous speeches in Western literature, put in their mind where their own self-interest lay. As Anthony put it after teasing the Mob with the wealth they might gain from dead Caesar’s will: “Now let it work. Mischief, thou art afoot, take thou what course thou wilt!”

It didn’t end well for Brutus and his henchmen. Not may it for those Senators.

But back to work,

Justice Kavanaugh is still in his early fifties, a virtual baby in Supreme Court Justice years. He and the other youngster, Justice Gorsuch, also in early fifties, may be the closest thing we can hope for as far as a youth movement on the Court that may be prepared to align Constitutional interpretation with modern technology.

Let’s talk about that.

In my last segment, I lay some groundwork for a direction I believe the Supreme court may take to find its way out of the Katz case “expectation of privacy” quicksand in which they are mired.

As you will recall, it was the Katz case which found that a listening device attached to the outside of a telephone booth to capture the conversation of a number’s runner violated a person’s “reasonable expectation of privacy” and therefore, his rights against illegal search and seizure under the Fourth Amendment. The “expectation of privacy” test was a creation of the Court. And has been in use for fifty years or so.

My discussion was based on Justice Scalia’s attempt in U.S. v Jones (government surreptitiously attached GPS device to suspect’s car) to “return to the future” in Fourth Amendment analysis by reintroducing the concept of “property rights.” The “trespass” to property rights as a basic underpinning for the Fourth Amendment was in turn discussed by individual justices in last term’s seminal case on privacy rights, Carpenter v. United States.

Carpenter was suspected of committing a string of robberies in Detroit. The FBI used a court order (not a Search Warrant) similar to a subpoena to gain access to data about his cell phone use from service providers. Congress had, through legislation, prescribed this method for obtaining telephone records. They had attempted to balance the interests of privacy with the need of authorities to conduct investigations. What Congress is supposed to do.

The Feds were able to obtain 13,000 of Carpenter’s location points over a 127-day period. He was convicted. He appealed contending his rights under the Fourth Amendment were violated. The appellate court rejected his appeal finding he had no “expectation of privacy” in the data because he had willingly given the information to his carriers.

And that is the rub. The “expectation of privacy” test becomes problematical when the information is shared with others. If you willingly give information to strangers how can you say you have a reasonable expectation of privacy?

The Fourth Amendment protects the rights of citizens to be secure from unreasonable searches of “. . . their persons, houses, papers and effects.” As I have noted before, the crafters of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights were master wordsmiths. It pays to closely consider the words they used.

On its face those words protect a personal right (“their”) and a citizen’s physical integrity (“person”) and his or her property, (“houses, papers and effects.”) But what of location data continuously transmitted to a third-party carrier from one’s cell phone?

The Carpenter opinion, crafted by Chief Justice Roberts, begins by noting that in our nation of 326 million people there are 396 million cell phone users. It acknowledges “While individuals regularly leave their vehicles, they compulsively carry cell phones with them all the time. A cell phone faithfully follows its owner beyond public thoroughfares and into private residences, doctor’s offices, political headquarters and other potentially revealing locales. . . Nearly three-quarters of smart phone users report being within five feet of their phones most of the time, with 12% admitting that they even use their phones in the shower.”

The court then dramatically observed, “Accordingly, when the Government tracks the location of a cell phone it achieves near perfect surveillance, as if it had attached an ankle monitor to the phones’ user.” Furthermore, it can go back in time to retrace a person’s location for as long as the carrier retains the records, normally five years.

The constitutional problem, as noted above, is that none of the words of the Fourth Amendment applies. Neither does the “expectation of privacy” test as it had been interpreted prior to the Carpenter decision. The information sought by the FBI was in the possession of a third party. It had been willingly given over. It is not property.

Or is it?

Chief Justice Roberts did acknowledge what Justice Scalia had argued in Jones.

“For much of our history,” Justice Roberts wrote, “Fourth Amendment search doctrine was ‘tied to common-law trespass’ and focused on whether the Government was physically intruding on a constitutionally protected area.” But, he added, the Katz case held that the Fourth Amendment protected the privacy of “people, not places.”

Chief Justice Roberts opinion went on to conclude that the location data was protected under the “expectation of privacy” doctrine. But it was a struggle for him to arrive at such a conclusion. Two Supreme court cases from the modern era had held information in the possession of a third party was not covered by the “expectation of privacy” test. These had to be overruled.

And he even went to find that the order obtained pursuant to the legislation passed by Congress was not based upon the Probable Cause standard required by the Fourth Amendment.

Four separate and strong dissents were penned by Justices Kennedy, Thomas, Alito and Gorsuch. And in these opinions the constitutional basis of the Katz “expectation of privacy” test is challenged and a different pathway to the future is hinted at.

Many of the Justices expressed concern over how the law will keep abreast of rapidly changing technology.

Justice Roberts quoted a Justice from early in the last century who, when considering innovations in airplanes and radios, wrote the Court must tread carefully to ensure they do not “embarrass the future.”

Justice Kennedy, however, in response said, “perhaps more important, those future developments are no basis upon which to resolve this case. . . the court risks error by elaborating too fully on the Fourth Amendment implications of emerging technology before its role in society has become clear. The judicial caution, prudent in most cases, is imperative in this one.”

Justice Kennedy went on to argue the traditional position that there is no “expectation of privacy” in material in the hands of third parties.

Both Justice Kennedy and Alito worried over the impact on investigations of corruption and Terrorism. They said, “The court’s new and uncarted course will inhibit law enforcement and keep defendants and judges guessing for years to come.”

And Kennedy noted, “this case should be resolved by interpreting accepted property principles as the baseline for reasonable expectation of privacy.”

Justice Clarence Thomas, in a brilliant opinion, did an exhaustive historical analysis of the Fourth Amendment and called for the overruling of Katz test. “Until we confront the problems with this test, Katz will continue to distort Fourth Amendment jurisprudence.” He went on to relate how Jurists and commentators, have called the Katz cases, “an unpredictable jumble,” a mass of contradictions and obscurities;” “all over the map,” “riddled with inconsistency and incoherence,” among other descriptions.

It is also historically significant, he pointed out, that the Katz decision was issued in the interim between the Griswold case in 1965, the first case recognizing an implied Right to Privacy and Roe v Wade in 1973 extending that newly recognized right to abortion. Privacy was, as Justice Thomas noted, “the organizing constitutional idea of 1960s and 1970s.” He went on to say, however, that “The organizing constitutional idea of the founding era, by contrast, was property.”

He and the other justices criticized how Judges frequently use the looseness of the Katz test to impose their own views on society. The cases, Thomas wrote “bear the hallmarks of subjective policymaking instead of neutral legal decision-making.” The application of the Katz test about societies expectations of privacy, “bear an uncanny resemblance to those expectations that this Court considers reasonable.” He said, “self-awareness of eminent reasonableness’ is not really a substitute for democratic election.” In other words, the Court once again walks into the trap of substituting their own personal views instead of deferring to the democratic process.

Justice Alito elaborated on this theme by criticizing Robert’s opinion and its easy willingness to emboss new standards on the subpoena process.

“By departing from these fundamental principles, the Court destabilizes long-established Fourth Amendment doctrine. We will be making repairs – or picking up the pieces- for a long time to come.”

Going all the way back to the Judiciary act of 1789 Justice Alito traced the origins of the subpoena power and established that never before had it been subject to Fourth Amendment analysis. It was never about the government trespassing on property. Rather, it was about the ability to investigate crime by requiring the production of records.

“The desire to make a statement about privacy in the digital age does not justify the consequences that today’s decision is likely to produce.”

In sum, Justice’s Kennedy, Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch each in separate dissenting opinions criticized the use of the Katz case and the “expectation of privacy” test. They either argued that it does not apply or should be dispensed with completely. And each returned to the original “property/trespass” based foundations of the Fourth Amendment.

But in the last segment it was Justice Gorsuch who may have pointed a possible way to the future.

He argued that data even in the hands of a third party like a carrier can still be “your” property. He detailed all the different property interests one can have in property held, even voluntarily, by another and that your Fourth Amendment protections can apply, not to sustain an amorphous “expectation of privacy”, but as a property interest which is protected from government intrusion.

His opinion provides a road map away from the monster Katz “expectation of privacy” test and a way forward.

By looking back.

We will have to wait for future decisions to see if the court follows his direction.

For more Cline on the Constitution and other writings by Phil Cline, visit philcline.com