This Week’s segment of Cline on the Constitution

Voting

The process of casting a vote is changing. Who, when, and how is an accident of location. It can be vastly different from state to state.

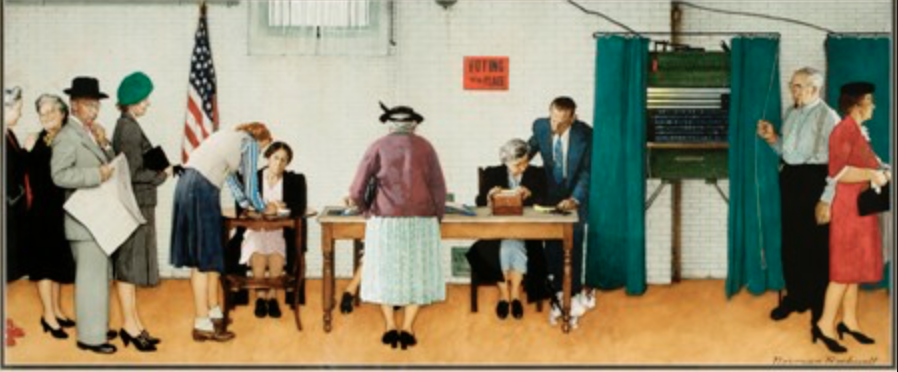

The image of an adult citizen showing up at the polls on election day, being handed a ballot, retiring to the voting booth to cast his or her ballot is no longer accurate.

There is no real date to appear at the polls. Absentee ballots are counted weeks before and weeks after the election date. Nor is it required that one casts one’s own ballot. Anyone, and I mean anyone, may “harvest” a vote. They can pick up an absentee ballot from a voter and cast it for them. And, at least in California there is no interest or inclination to investigate voter fraud by the Attorney General or the Secretary of State at least as long as their party is in power.

In California and across the nation, the right to vote is being extended to felons, non-citizens, the mentally infirm, even prisoners. Which if one considers a local election for Sheriff, may indeed put the inmates in charge of the asylum. And election officials are severely restricted from asking for a valid identification. One must have identification to cash a check, but not to vote.

And with the changes are legal challenges to voting. Last term the Supreme Court issued a number of opinions concerning voting and some important cases on the issue are on the court’s docket this term, including a challenge that might finally end the time-honored practice of gerrymandering.

This post and the two to follow will report on the court’s decisions last term and make some modest predictions about where I think these issues will go.

First, the Basics:

The original Constitution drafted by our framers had no reference to the right to “vote.” Qualifications and other issues related to voting were left up to the individual States. Some States excluded non-landowners from voting, others restricted voting based on religious beliefs, gender, or race. By the middle of the nineteenth century, however, these arbitrary barriers to voting were being dismantled.

The Fifteenth Amendment prohibited denying the right to vote based on race; the Nineteenth Amendment did the same for gender; the Twenty-Fourth eliminated poll taxes, and the Twenty-Sixth insure the right to vote for persons over the age of eighteen.

The Supreme Court for many decades under the “political question” doctrine deferred the resolution of issues related to voting to the other branches of government. That began to change in the 1960s. The best known of these early cases was Gray v. Sanders in which Justice Douglas’s opinion overturned a county based primary system because it diluted the voting power of urban areas. He wrote: “the conception of political equality from the Declaration of Independence to Lincoln’s Gettysburg address, to the Fifteenth, Seventeenth, and Nineteenth Amendments can mean only one thing – one person, one vote.”

Within a short time, the Court issued over a half-dozen opinions striking down state drawn district lines. And in 1965, Congress passed The Voting Rights Act which protected voting rights, and put certain states and jurisdictions under a Federal pre-clearance requirement for any changes to local voting procedures. Part of this act was eventually (in 2013) held unconstitutional because Congress repeatedly failed to update which jurisdictions were subject to federal control even though demographic changes made the continuing federal oversight irrational. (for more on these issues see previous posts.)

Now for the cases decided last term:

The first of the cases was decided last term was Minnesota Voters Alliance v. Mansky.

It’s not unusual for the Supreme court to be behind the times when it comes to discussions of technology and changes in society. Given the rapid changes, in some ways, the Mansky case is quaint and antiquated.

It’s discussion centers on polling places and attempts by a State government to regulate conduct and speech at the polls. The traditional justification is to protect the voters from undue influence by banning the rough and tumble of politics from the sacred precinct where votes are cast. In the Court’s language, “an island of calm in which voters can peacefully contemplate their choices.”

Mansky was a 7-2 decision. The opinion was penned by Chief Justice John Roberts. The state sought to regulate the wearing of “political” apparel at the polling place.

The law was enacted in Minnesota in the 19thcentury in response to so-called “chaotic” conditions where “crowds would gather to heckle and harass voters who appeared to be supporting the other side.” Where polling places became “highly charged ethnic, religious, and ideological battlegrounds in which individuals were stereotyped as friend or foe, even on the basis of clothing.”

Hmmm. Sounds familiar.

It’s not difficult to conjure up modern examples of what would be prohibited. Make America Great Again hats for sure, rainbow flags, one would think. Tee shirts depicting aborted babies, pink pussy hats? But where is the line? And, always the question, who gets to say where the line is? Do we really want federal judges to do it and thereby become even more political than they already are?

Thankfully, the court in this instanced said No.

The Court struck down the law in Mansky as not being specific enough in its definition of what was banned by words like “political.” By banning political apparel, it impinged on Freedom of Speech. Consistent with First Amendment jurisprudence it ruled the State may regulate campaign activities, (or conduct) at polling places, but found the inclusiveness of the language violated freedom of speech.

So far, so good.

But in a couple of ways the case is another “judicial head in the sand” decision.

First, it gives too short shrift to the reasons the legislation was enacted. Things haven’t really changed. People still abuse other people, and improperly invade every public space in the most vulgar and vile manner. Hells Bells, even a group of Christian high school kids can’t gather in the Nation’s Capital to support the Right to Life movement, without being harassed by a group of Black adults spewing hatred and a nutty snaggle tooth man pounding his drum in a teenager’s face.

Second, in point of fact, developments in voting I outlined in my introductory paragraphs are harbingers of the future. And the inevitability of online voting. As we move closer to what many said was impossible: “Direct Democracy” in which the voting public can decide in an instant whether to approve or disapprove a proposition, an initiative, even a candidate, indeed any law.

Maybe, some might even begin to question the need for legislatures and legislators. Afterall, we all can with a push of a button, (or rather the click of a mouse) make the decisions instantaneously. And of course, oldsters like me, might ask but what of representative democracy? And the new generation might answer: But, do we have that now? A dysfunctional Congress, corrupt and mindless state legislatures, all in the hands of a few legislative and committee leaders? Who secure their sinecure by raising and disbursing campaign donations?

Uh, . . . maybe someone should listen while the Supreme Court is busy answering questions no one may be asking anymore.

For earlier posts or more writing by Phil Cline visit philcline.com