In Abbott v. Perez, The Supreme Court slapped a federal district court with a much-needed douse of cold water in an attempt to wake them up, force them to embrace reality for once and have them return to their lane in the governance scheme set out in the Constitution. Abbott is the second case on voting decided by the Supreme Court last term I wanted to bring to your attention. It is one of a series of cases which seem destined to set up a blockbuster decision on Gerrymandering most scholars anticipate will be decided this term.

This case involved a redistricting plan. Under the Constitution re-drawing district lines for congressional offices is a power left to the States and not delegated to the Federal Government. However, the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment passed after the Civil War, forbids “Racial Gerrymandering.” And under the express power to legislate enforcement of the Fourteenth Amendment the Congress passed the Voting Rights Act.

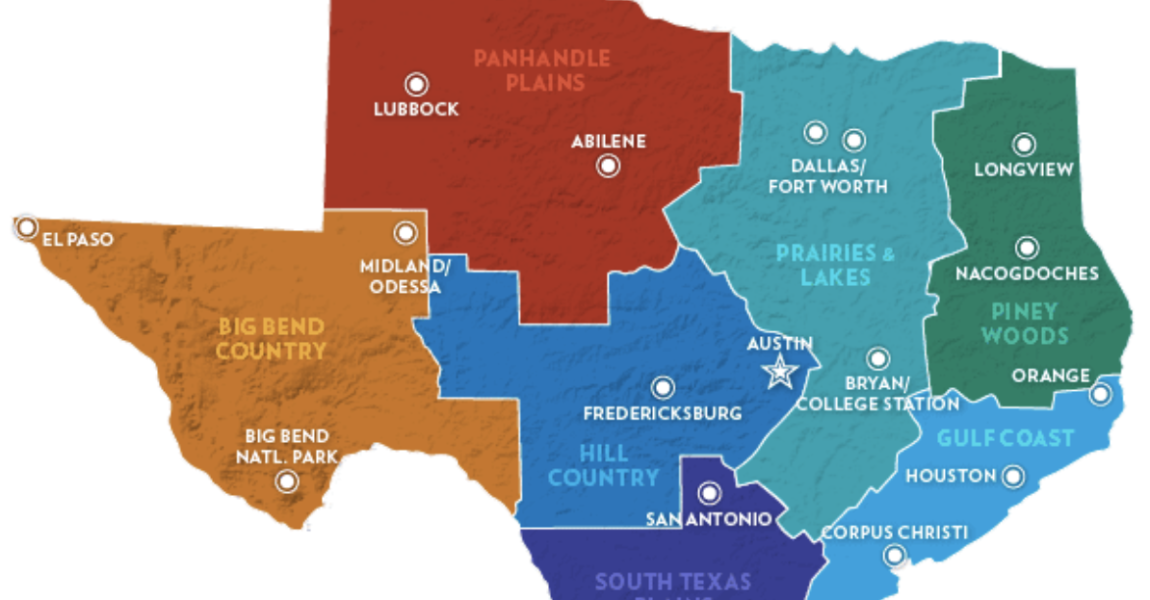

After the 2010 census, the Texas State Legislature set out to redraw district lines.

A plan was passed in 2011 but was tied up in court and never used. In 2013, after the Shelby decision (discussed in a previous post) invalidating part of the Voting Rights Act, the state legislature attempted to resolve the issue by approving a redistricting plan modeled on one the district court itself had approved. But, of course, that plan was also attacked. As the Supreme court said, “The Legislature had reason to know that any new plans it devised were likely to be attacked by one group of plaintiffs or another.” Sadly, that is a modern truism about any attempts to govern by a legislative body. Somebody is going to sue, and some federal district court somewhere is going to figure they know better how to govern than those elected to do the governing.

In yet another example of overreaching arrogance by a lower federal district court where no action of a government ever seems to be satisfactory, this new plan was struck down because the federal court decided the State had not satisfied the court of their good intentions.

In an opinion crafted by Justice Alito, the Supreme Court did two things which to one unschooled in the law may seem minor, but which any lawyer will recognize as important.

First, it reversed the lower court’s assignment of the burden of proof. Instead of placing it on the government, it placed it back where it belongs with the plaintiff, the person or entity bringing the law suit. The lower federal court without any authority to do so had decided the government had to show that they had somehow “purged” and “cured” the taint of the 2011 plan, a plan that had been “alleged” to be discriminatory and a plan that wasn’t even used. The lower court went further and in a brazen display of judicial interference in the legislative sphere, it required the legislature to conduct its deliberations in a way the court approved. Reminds one of a court requiring a showing that the taint of a statement by a candidate in an election must somehow be cured before the court can even read, much less consider the actual legislation before it. It’s like federal courts see themselves as high priests requiring a trip to the confessional by the other supposedly co-equal branches of government for an expiation of sinful thoughts.

Second, the Supreme Court confirmed the principle that should always apply to official actions by those democratically elected to govern. That is that their acts are presumed to have been done in good faith. The federal court erred in ignoring the evidence that in fact the Texas state government had acted in good faith.

In applying the law to the case, the Court reiterated the general rules regarding redistricting challenges. It must be shown by the person or entity attempting to block the redistricting, 1) is a geographically compact minority population, that is a majority in the district. 2) There is political cohesion among members of the group and 3) bloc voting by the majority is taking place to defeat the minorities preferred candidate. And after all that, then the plaintiff must prove under the totality of circumstances the district lines dilute the votes of the minority group.

In the Abbott case, the tests were not met. And it was plaintiff’s burden to make the showing. In other words, to prove what they alleged.

In elections across the land, attempts to draw district lines face multiple challenges no matter what efforts the local government expends to do the redistricting in a fair way. Statistical models are used and provocative language about voter suppression and racism are inevitably pressed at every opportunity. That is all find and dandy. So be it.

But in Abbott the Court reaffirmed a basic principle. It is one we should be applying in our general public actions and statements. If you allege it, then, by God, prove it!

Don’t accuse a person of something and then adopt the presumption that it must be true. Don’t require a person prove they didn’t do the wrong or, worse, think the wrong thoughts at the wrong time. No. It’s your allegation. Prove it. It’s the legal equivalent of saying, “Put up or shut up.”