Cline on the Constitution – the Census Question and the Politization of the Court

Summer vacation is over, and the Supreme Court’s traditional opening for the new term the first week of October draws nigh. With a brutal campaign for President unfolding the stage is set for what could be a turning point for the Supreme Court. Will it continue on its current path or return to its role of a fair and unbiased interpreter of the Law? And will its path be selected on legal principle or out of fear of the consequences of its decisions?

We will attempt to answer this question over the next few months as decisions come down. For now, I’m going to spend longer than usual on my opening piece setting up a peek through the window into the politicization of the Federal Court System.

Two strains of popular wisdom concerning the role of the Judiciary exist.

The first is that the Court is above politics, decides cases only on the law and eschews the political power contests entrusted by the Framers to the Congressional and Executive branches. Judges and Justices are fond of propounding this idealized version of their role in society.

The second is that the Court is just as apt to have their finger in the air testing the political winds as a small-town southern Sheriff. Increasing numbers in both the population at large and (though they prudently would never say it out loud), the legal profession ascribes to this view.

The first view, that the Court is an unbiased arbiter of the law is a canard. It has never been completely true. However, the Court for most of the Republic’s history tried to keep federal courts from being overtly political. Their efforts were aided by adherence to self-imposed rules of restraint in which they insisted Federal courts defer to the political branches, the Congress and Presidency, when they were tempted to step into areas in which unelected Judges have little expertise, and absolutely no competence.

Last term it became clear there is no curtain to hide behind anymore. The decisions of a great many Federal District and Appellate Courts were consistently political and biased. And the Supreme Court is gradually being sucked down into the same quicksand. In my opinion, it’s no one’s fault but their own.

Chief Justice John Roberts, someone I have long admired, has proved surprisingly susceptible to being compromised. To use his own term his decisions on high stakes political cases are merely a “pretext” to avoid having himself or his Court labeled too Conservative. And like most conservative thinkers who make sincere attempts to compromise it is never good enough for those who want their very soul. It is inevitably a Faustian bargain.

One incident last term highlighted the hypocrisy. Chief Roberts called out the President for implying federal court decisions could be predicted based upon which President appoints the federal judge.

This was only shocking to the unthinking and willfully uniformed. Even the News media reports who appointed the federal judge when a decision is published.

What made it controversial is the Chief jumping into the fray and maintaining the opposite. He said, “We do not have Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges. What we have is an extraordinary group of dedicated judges doing their level best to do equal right to those appearing before them. That independent judiciary is something we should all be thankful for.”

Only were it true.

Before the ink dried federal courts provided persuasive evidence to the contrary. In response to yet another challenge to the President’s fruitless attempts to address illegal immigration, on one side of the country, a federal judge refused an application for a nationwide injunction on newly propounded asylum rules. On the other side of the country a federal judge was only too eager to do the opposite and grant the injunction.

Guess which one was appointed by Obama and which one was appointed by Trump. If you know the answer without asking, then maybe the President had a point.

And then there are the Members of the United States Senate who not only have adopted character assassination into its Advice and Consent role, as it did with the Kavanaugh and Thomas hearings, but now overtly threatens the Supreme Court with consequences if it decides a case in a manner the Senators disagree with. These same members of the Senate actually filed court briefs and issued a public warning to the Supreme Court not to decide a pending case by upholding the Second Amendment to the Constitution. They expressly threatened to restructure the Supreme Court if the Court decided the case contrary to the Senator’s wishes.

If one has lived an honorable distinguished life in the law only to be placed under the most scurrilous attacks by false accusations, do you not think the individuals would take such threats seriously? Is there a chance they may modify their decisions out of fear? Would it surprise anyone? Is not instilling fear the ultimate goal of confirmation by destruction?

Our Chief Justice, whom I have long admired for his intellect and legal mind may in fact be the latest example of what the threats will do to otherwise reliable conservative voices on the Court.

His latest opinion on the issue of a census question invites the conclusion that the Court will engage in the most political of decisions and damn settled law along the way. And in the process open the Court to even more fervent political manipulations in the future.

In Department of Commerce vs. New York the easy compromise of legal precedent and principle in service to political expediency is on stark display.

The issue involved in the case was whether a question would be propounded in the next census about the citizenship of persons being surveyed.

First the basics.

The Constitution requires an “Enumeration” of the population every 10 years to be made “in such Manner” as Congress “shall by Law direct.” Congress, in turn delegated the task of conducting the decennial census to the Secretary of Commerce “in such form and content as he may determine.”

The Supreme Court has repeatedly recognized that the census has been used to gather information on race, sex, age, health, education, occupation, housing and military service as well as other subjects as varied as radio ownership, age at first marriage and native tongue. The Census Act obliges the Secretary to keep individual answers confidential, including from other governmental agencies.

In the 22 decennial censuses from 1790 to 2000 a question about citizenship or place of birth had been asked.

In 2010, the question was not asked.

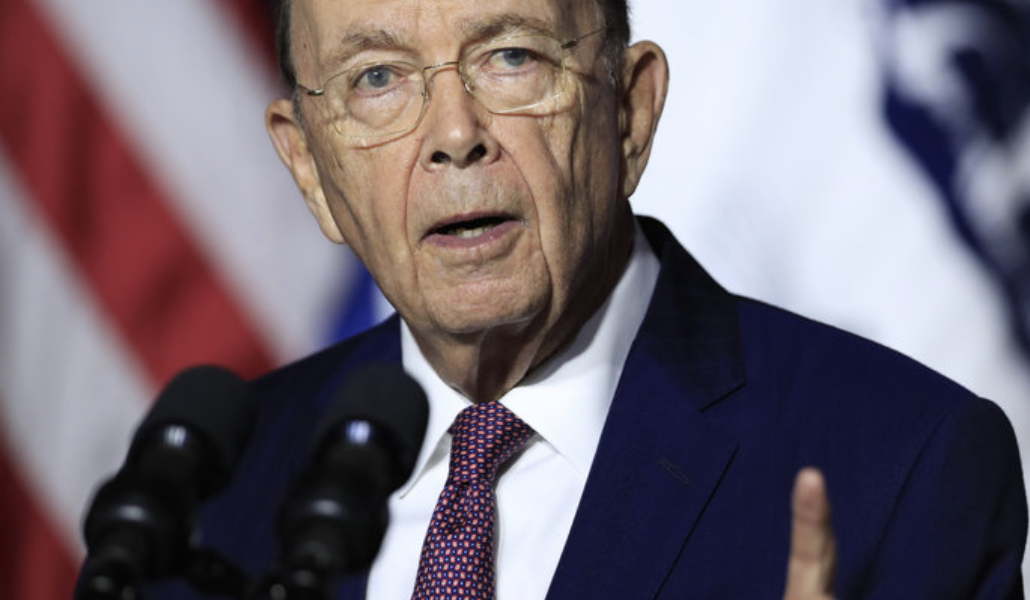

In March of 2018 the Secretary of Commerce, Wilbur Ross, announced the question would be reinstated in the 2020 census.

While, there was much gnashing of teeth, the most strident argument was over whether the question would depress response rates from non-citizens. Given the fact that untold millions of illegal aliens reside within the United States and untold billions of dollars as well as dozens of Congressional seats would be allocated by the demographic information collected in the census, there was an understandably intense interest in banning the question from being asked if there was a chance it would change the bottom lines.

Secretary Ross in writing maintained that he “carefully considered” the possibility that reinstating the question would depress response rates, but that after evaluating the “limited empirical evidence”, he concluded it was not possible to “determine definitively” whether inquiring about citizenship in the census would materially affect response rates. He went on to note the long history of the citizenship question on the census as well as the fact that all major democracies such as Australia, Canada, France, Indonesia, Ireland, Germany, Mexico, Spain and the United Kingdom inquire about citizenship in their censuses.

One may not agree. But it was his call to make and he made it. So far so good.

Then the legal challenges began. And the Federal Courts were only too pleased to intervene. “Hold on” they in effect said. “You can’t govern, you can’t make decisions without getting our august approval first.”

And that is the real rub to the case. The import of the decision was not whether the Secretary made the right call. Rather it is what roll the framers envisioned for the Courts in such situations?

By a 5 to 4 vote, with Chief Justice Roberts penning the majority decision the case was returned to the lower court for further proceedings to clarify the decision-making process of the Secretary. Everyone, including the justices on the Court, knew that ordering such an action killed the question because there was too little time to fight the legal battle and meet the statutory deadlines for conducting the census.

Contrasting the Roberts opinion with the opinion of the dissenting justices leaves little doubt that the decision was a political one.

Leading off, the Court declined to involve itself in the question regarding the depression of response rates. “We may not substitute our judgement for that of the Secretary, but instead must confine ourselves to ensuring that he remained within the bounds of reasoned decision making.” So, yep, the Secretary can make the decision like the law empowers him to do, but the reasoning better be up to the Court’s standards.

The Court felt it had to address two questions.

The first was whether his course of action was supported by the evidence before him. The Court found it was. Remember that. At this point the Court has said the Secretary’s action was legal and constitutional and had an evidentiary basis to take the action he did. The court said, “The choice between reasonable policy alternatives in the face of uncertainty was the Secretary’s to make. He considered relevant factors, weighted risks and benefits, and articulated a satisfactory explanation for his decision.” What, pray tell, could be the problem?

It’s in the second question which is the strange one. Whether the Secretary’s rationale was “pretexual”?

Chief Justice Roberts noted that the lower court had found the evidence established the Secretary had made up his mind to reinstate a citizenship question well before he took office. And he the Chief agreed that there is nothing objectionable or even surprising in this. At least, as Roberts says, “up to a point.”

The Court said, “It is hardly improper for an agency head to come into office with policy preferences and ideas, discuss them with affected parties, sound out other agencies for support, and work with staff attorneys to substantiate the legal basis for a preferred policy. The record here reflects the sometimes-involved nature of Executive Branch decision making, but no particular step in the process stands out as inappropriate or defective.”

Yep. This is how the art of governing works. So, what’s the problem?

Evidently, something didn’t sound quite right to the Chief Justice. After reviewing thousands of emails and over 12000 pages of other documents, he said, “We are presented with an explanation for agency action that is incongruent with what the record reveals about the agency’s priorities and decision-making process.”

He felt that the Court “must demand something better than the explanation offered for the action taken in this case.”

Huh? Talk about overreach!

The dissent led by Justice Thomas, Gorsuch and Kavanaugh was brutally direct in their criticism of majority decision.

The dissenting opinion states, “The Court . . . for the first time ever . . . invalidates an agency action solely because it questions the sincerity of the agency’s otherwise adequate rationale.”

And they went on say the decision echoes “the din of suspicion and distrust that seems to typify modern discourse.” In other words, the Court has now got down in the mud with everyone else.

The Justice continued, “The Court’s holding reflects an unprecedented departure from our deferential review of discretionary agency decisions.” And a warning is issued about future cases and the impact that they will have on the Court. “It is not too difficult for political opponents of executive actions to generate controversy with accusations of pretext, deceit, and illicit motives. Significant policy decisions are regularly criticized as products of partisan influence, interest-group pressure, corruption, and animus. Crediting these accusations on evidence as thin as the evidence here could lead judicial review of . . . to devolve into an endless morass of discovery and policy disputes.”

And here is the key problem with Roberts decision. The dissenting Justices say, “Unable to identify any legal problem with the Secretary’s reasoning, the Court imputes one by concluding the at he must not be telling the truth.” He goes on to say, “The Court engages in an unauthorized inquiry into evidence not properly before us to reach an unsupported conclusion.”

There is one last acknowledgement of how governing actually works in real life. “None of this comes close to showing bad faith or improper behavior. Indeed, there is nothing even unusual about a new cabinet secretary coming to office inclined to favor a different policy direction, soliciting support from other agencies to bolster his views, disagreeing with staff, or cutting through red tape.”

Well, yes. That’s why we elect people in the political branches! And why unelected federal judges should confine themselves to the law.

Otherwise the prophesy left us by the dissenting justices will surely come true.

They said, “With today’s decision, the Court has opened a Pandora’s box of pretext-based challenges in administrative law. . . Having taken that step, one thing is certain: This will not be the last time it is asked to do so. Virtually every significant agency action is vulnerable to the kinds of allegations the Court credits today.”

And he continues,

“Now that that the Court has opened up this avenue of attack, opponents of executive actions have strong incentives to craft narratives that would derail them. Moreover, even if the effort to invalidate the action is ultimately unsuccessful, the Court’s decision enables partisans to use the courts to harangue executive officers through depositions, discovery, delay and distraction. The Court’s decision could even implicate separation-of-powers concerns insofar as it enables judicial interference with the enforcement of the laws.”

Fear.

He ends with a forlorn hope. About this decision he says since it is such a departure from traditional principles of administrative law, “Hopefully it comes to be understood as an aberration — a ticket good for this day and this train only.”

I’m afraid not.

For more writings by Phil Cline visit my secure website at philcline.com