Self-Defense against the government?

The nature of the Coronavirus has led every level of government; City, County, State and Federal; to take emergency action to mitigate the impact on society. And that includes intruding upon civil liberties.

There is no longer enough room to list all the ways our freedom is being restrained. There are many. They range from illegal stops by police on cars with out of state license plates, to restraints on the exercise of religion, to prohibitions on engaging in business and in a chilling development encouragements, like the one issued by the Mayor of Los Angeles, offering monetary awards for neighbors to spy and report on their neighbor.

These orders restraining civil liberties with threats of arrest, monetary sanctions and even confiscation of property are daily being issued by officials lower and lower on the rungs of governmental power. It’s one thing for the President to exercise Emergency Powers in a crisis, or even a Governor, it is a wholly other matter for some small city Mayor or city councilman or some factotum in the back waters of a county health department to exercise control over our daily lives with threats of jail and fines for using the public roads or attending houses of worship.

One development piqued my interest.

After a decade of police being disarmed and hamstrung in their interactions with criminals, courts across the land, and in our own county, have taken it upon themselves, against the advice of law enforcement experts, to issue orders for the release from jails of dangerous felons and other criminals.

There is a delicious irony here. Instead of relying on the competence of Sheriffs to run the jails and protect the inmates in their care, judges release dangerous criminals out of a misplaced concern for the virus being spread in the jails. And at the same time, we have small town mayors threatening to refill the jails with law abiding citizens who choose to worship together or play basketball at a local park. I suppose there will be plenty of room to jail our citizens since so many of the criminals will be out on the streets.

Beyond the irony, it does hold the potential for civil unrest.

At the same time these orders have put the public in danger, there have been efforts to keep citizens from purchasing guns and ammo to protect themselves.

I thought it would be interesting to revisit the Second Amendment foundations with this potential governmental overreach and the danger of civil unrest in mind.

Historically there are two foundations to the Right to Bear Arms protected by the Second Amendment to the Constitution. Most serious commentary regarding the right to bear arms and most cases decided by the Supreme Court center on the first foundation, that is whether someone should be able to arm themselves for self-defense against criminals or for hunting and sporting purposes.

For example during oral argument in District of Columbia v Heller, the case decision which debunked the theory that the Right to Bear Arms was solely coupled to the operations of Citizen Militias, Justice Kennedy asked a poignant question, whether in the context of Early American society the right had to do with “the concern of the remote settler to defend himself and his family against hostile Indian tribes and outlaws, wolves and bears and grizzlies and things like that?”

Heller decided in 2008 and McDonald v Chicago decided in 2010 confirmed this basis. The Right to Bear Arms is tied to the right to individual self-defense.

But there is also a second foundation, seldom discussed. The Right to Bear Arms is tied to a right of self-defense against governmental oppression.

Modernly, arguments that it may necessary to protect oneself from repressive measures by the government have for the most part been relegated to fringe anti-government, Patriot, and survivalists’ movements. They are seldom taken seriously and almost never find their way into briefs filed with the Court nor in case decisions issued by the Court. There is no need because Courts have been quick to hear and decide cases regarding the slightest infringement on the Bill of Rights. Overreaching by governmental entities is quickly restrained.

Nevertheless, there is a basis here. Always has been. And we may find it relevant if the current Emergency is prolonged and if increasingly severe restraints on freedom and penalties for non-compliance are put in place.

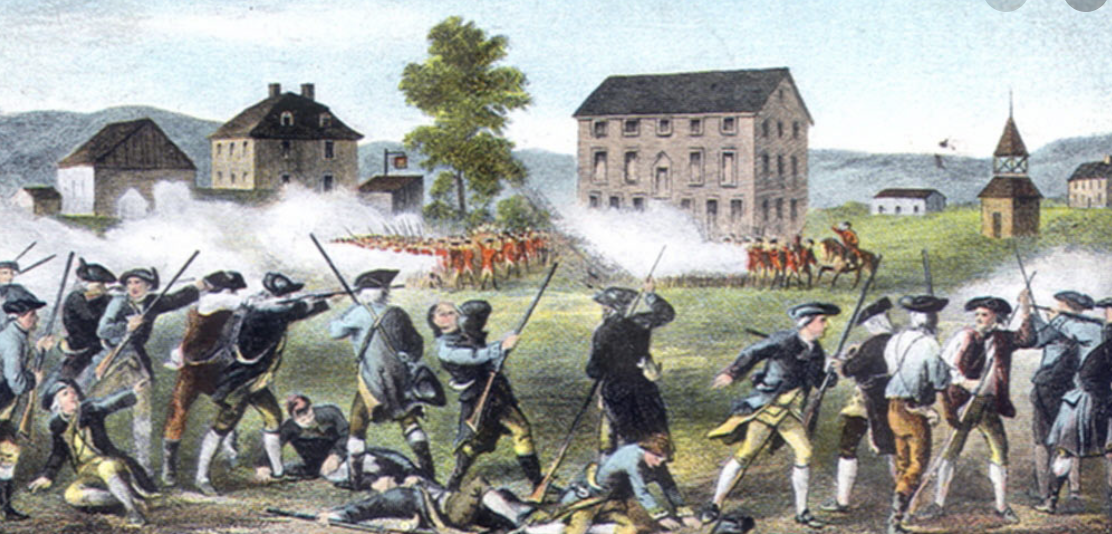

For Americans this foundation to the Right to Bear Arms can be traced to April 19, 1775, when a group of Americans bearing their own firearms stood before a contingent of British Redcoat soldiers representing the greatest military power on Earth. These Americans bore their own private arms on the town common of Concord, Massachusetts. And as Ralph Waldo Emerson’s said: “Here once the embattled farmers stood / And fired the shot heard round the world.” The use of those guns launched the American Revolution against a repressive government.

When years later, in 1789, The Founders drafted the Bill of Rights they recalled the British efforts to confiscate private firearms from the American colonists and that those same colonists used such firearms to start and help win the American Revolution.

The leading (and only) judicial precedent on the Statute known to the American Founders involved the prosecution of Sir John Knight in 1686 in England. A Statute prohibited persons “from going or riding armed in affray of peace,” and the charges alleged Knight “did walk about the streets armed with guns, and that he went into the church of St. Michael, in Bristol, in the time of divine service, with a gun, to terrify the King’s subjects. The case was tried and Knight was acquitted. The Chief Justice presiding over the courts said the meaning of the Statute “was to punish people who go armed to terrify the King’s subjects.”

Knight was found not guilty. Why? He had walked in the streets and gone into a church service with a gun. But nothing in the evidence suggested that he had threatened anyone, brandished a weapon, or started a fight.

The foundation for the ruling upholding his right to bear arms had a historical context.

The Restoration of the Stuarts in 1660 entailed measures to disarm the monarchy’s political enemies. In 1662 Charles II passed a bill empowering official “to search for and seize all arms” possessed by a person judged to be dangerous to the peace of the kingdom.”

The reason for such laws, William Blackstone, universally acknowledged as the foremost authority on British law, observed, was “prevention of popular insurrections and resistance to the government, by disarming the bulk of the people . . .”

James II continued the same repressive policies, which eventually sparked the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

The Declaration of Rights of 1689, sparked by the revolution, listed the ways that James II attempted to subvert “the Laws and Liberties of this Kingdom,” including: “By causing several good Subjects, being Protestants, to be disarmed, contrary to law.”

Blackstone maintained that the declaration contained “absolute rights” of “personal security, personal liberty, and private property” to wit, “the natural right of resistance and self-preservation, when the sanctions of society and laws are found insufficient to restrain the violence of oppression.”

The Americans would hold tightly to this fundamental right of Englishmen when their freedom was threatened and violated by George III.

As the Supreme Court said in McDonald, “The right to keep and bear arms was considered . . . fundamental by those who drafted and ratified the Bill of Rights.”

In The Federalist No. 46, James Madison heralded “the advantage of being armed, which the Americans possess over the people of almost every other nation,” adding: “Notwithstanding the military establishments in the several kingdoms of Europe, . . . the governments are afraid to trust the people with arms.”

George Mason opined that “when the resolution of enslaving America was formed in Great Britain, the British Parliament was advised . . . to disarm the people; that it was the best and most effectual way to enslave them.”

The Framers understood that trust in government, any government, not to abuse its power over its citizens, not to compromise on their rights, was dangerous.

Is it okay for Government to compromise our rights in an Emergency? It’s one thing to strongly encourage people in the interest of the greater good to restrain the usual exercise of their rights. In an Emergency. But by definition an Emergency is not a permanent state of affairs.

How long can rights be denied?

It cannot be gainsaid, that the virus is serious. Very serious. But the government is taking many of our liberties and shelving them. And in the name of it being an Emergency, not a lot of thought is being given to the implications and, importantly, exactly who has the power to take away our rights.

Questions always need to be asked.

First, when do we get our rights back and, second, what do we do if they aren’t given back? What if our liberties continue to be constrained for weeks, months, years? And who gets to make decisions on what freedoms we may exercise?

Are armed confrontations with the government possible if civil unrest is the result?

God, I hope not.

But to the Framers, in the context of their world, they understood it might one day be necessary.