Cline on the Constitution

Hey Oklahoma, A Deal’s a Deal! Or is it?

After my usual Summer hiatus, I am happily turning back to take a closer look at some of the Major Supreme Court cases decided last term. There are some good ones to explore before the new term opens in October.

Let’s start with something fun, the day half of the State of Oklahoma, in legal terms, kind of disappeared.

My family hails from Arkansas and proudly wears the moniker of “Arkie” and sports any sweatshirt emblazoned with a Razorback. However, many of my friend’s families who similarly immigrated West in the diaspora from the South and Midwest during the depression, respond, Steinbeck notwithstanding, and proudly proclaim, “Damn right I’m an Okie!”

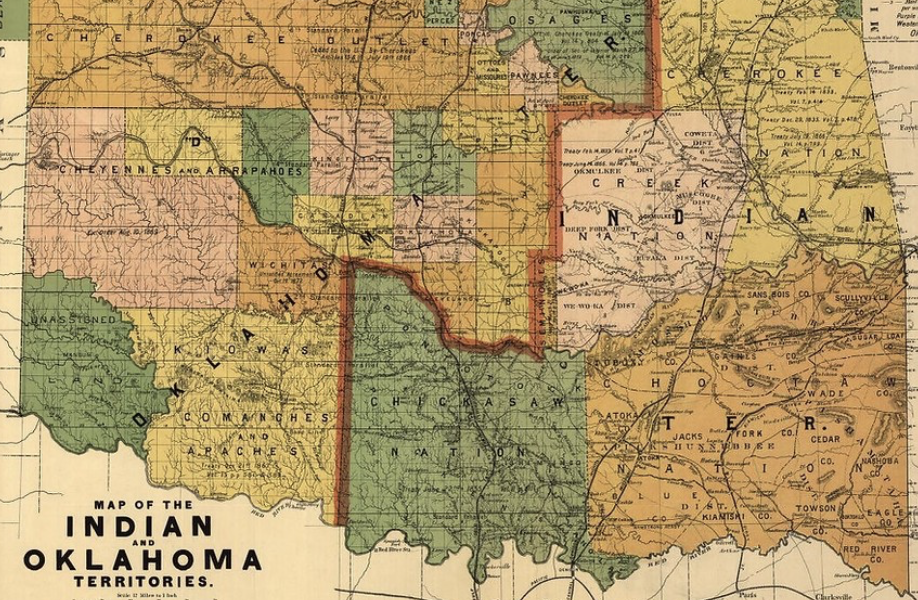

Well, whether they are a true “Okie” may depend on which part of the State of Oklahoma they came from since a recent decision of the Supreme Court that some 3 million acres, and possibly another 16 million acres, basically the entire Eastern portion of the State encompassing the city of Tulsa, is no longer the sovereign state of Oklahoma. But rather as I used to hear old folks from back there refer to as, “Indian Territory.”

In a 5-4 opinion crafted by Justice Gorsuch in McGirt v. Oklahoma in July of this year, the Supreme Court reach a rather surprising conclusion. In the words of Chief Justice John Roberts, ”. . . unbeknownst to anyone for the past century, a huge swathe of Oklahoma is actually a Creek Indian Reservation . . . .”

The salient facts of the case involve a Jimmy McGirt. He was convicted in Oklahoma State Court of molesting, raping and forcibly sodomizing a four-year-old girl, his wife’s granddaughter. He was appropriately sentenced to 1,000 years plus life in prison. So far so good. But it turns out that McGirt is a Creek Indian and he put forth the improbable defense that the State of Oklahoma had no jurisdiction to prosecute him in State Court. Sometimes when a defense attorney throws it against the wall, some of it actually sticks. The Supreme Court ended up agreeing with him.

The Court was deeply divided in its decision. Justice Gorsuch teamed up the liberal bloc of justices to form the majority while Chief Justice Roberts in an unusual role for him led the conservative wing in dissent.

The holding of the Majority is rather elegant in its simplicity.

Justice Gorsuch wrote, “Today we are asked whether the land these treaties promised remains an Indian reservation for purposes of federal criminal law. Because Congress has not said otherwise, we hold the government to its word.”

In other words, Justice Gorsuch is saying, “A Deal’s a Deal!”

The impact on Mr. McGirt, who was enrolled on the rolls of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma and who committed his crimes within what had once been designated the physical boundaries of the Creek reservation was that he was entitled to a new trial in Federal Court since the State Court had no jurisdiction over him. The Court did limit its ruling.

“Nothing we say today could unsettle Oklahoma’s authority to try non-Indians for crimes against non-Indians on the lands in question. Still . . . the State has no right to prosecute Indians for crimes committed in a portion of Northeastern Oklahoma that includes the city of Tulsa. Responsibility to try those matters would instead fall to the Federal government and Tribe.”

This was news to the city of Tulsa and a large portion of the State of Oklahoma which had for decades assumed the reservation no longer existed. A fact that Chief Justice Roberts and the other justices in the minority found, as one would expect, rather persuasive.

Let’s get some context from history gleaned from the case.

In 1833, the Creek nation, who once occupied what is now Alabama and Georgia, along with the other members of the so-called “Five Civilized Tribes” – the Cherokees, Chickasaws, Choctaws, and Seminoles were required to cede their ancestral lands in exchange for what became known as “Indian Territory.” The new land was located at the end of the Trial of Tears, today’s Oklahoma.

When the treaty of 1833 was signed, the United States government agreed that in exchange for ceding all their land east of the Mississippi river, “the Creek country west of the Mississippi shall be solemnly guaranteed to the Creek Indians.” The Boundary lines agreed to was located in what is now Oklahoma. And further, “no State or Territory shall ever have a right to pass laws for the government of such Indians, but they shall be allowed to govern themselves.”

There were some unique features to the treaty, one of which granted them actual property rights (land was held in communal fee simple) when most other treaties only gave Indian tribes “a right of occupancy.”

Certainly, the ownership of the land has since 1833 changed its character. In a way, considering the Tribe was at a severe disadvantage in terms of bargaining leverage, the leaders of the Creek Nation made some good decisions during the negotiations with the United States. As part of the bill granting them the new lands in the future Oklahoma, Congress made an offer that “. . . If they prefer it, the United States will cause a patent or grant to be made and executed to them for the same; provided always, that such lands shall revert to the United States, if the Indians become extinct, or abandon the same.”

Wisely, the Tribe accepted this offer which meant that not only would they have the promises of the treaty but would hold actual legal title to the lands. The grants of land were then given in “fee simple” to the Creek Nation. “Fee Simple” to every lawyer who has ever practiced law means one thing: ownership. The Creek Nation owned the land. Unfortunately, they later agreed to forfeit the communal ownership and divided the land into pieces owned by individual tribe members. And many of these were sold to persons unaffiliated with the Tribe.

But did/does the reservation of 1833 still exist? As to this question both the Majority and the Minority decision went through a detailed analysis of the process of “Disestablishment” and whether it applied to the Creek Reservation. I can’t do justice to these arguments in the space I have, but a few general principles can be gleaned to explain.

“Disestablishment,” which simply means the legal extinguishing of the reservation, was to most historians, inevitable. After the treaty was signed, major historical events occurred which made it impossible for the reservations to survive. First the Civil War (more on how it affected this particular treaty later) and then, after the war was concluded, the irresistible spur of new railroads and a repurposed Union army for a vast movement of the country westward. As the case points out by 1900 over 300,000 settlers had poured into Indian Territory (Oklahoma) and they outnumbered the Five Tribes by 3 to 1. It was also inevitable that the Congress would begin a process of passing laws that would weaken the hold on the land the treaties had granted.

The Supreme Court went along with the process and upheld these laws consistently over the decades in what became recognized as a process called, “Reservation Disestablishment.”

The real fight in the McGirt case was not over whether the reservation could be “Disestablished.” Fair or unfair, both the Majority and Minority opinions accepted there was no going back. Despite the promises in treaties, the process of Disestablishment, that is having selected reservations extinguished by acts of Congress, was and is accepted as a legitimate power of Congress. The fight in the McGirt case was over whether “Disestablishment” had to be express or could be implied.

Did the Congress have to say explicitly that the reservation was “Disestablished” or could it by numerous acts and laws passed and signed into law disestablish the reservation without explicitly saying so? Congress did pass a multitude of laws that eliminated the self-governing aspects of the Creek reservation as well as allowed the land to be broken up and sold off as well as other sanctions imposed on the nation for its affiliation with the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Unfortunately, the Five Indian Tribes collectively held over 8,000 slaves and signed treaties of alliance with the Confederacy and contributed forces to fight along with the Rebel troops. (I guess it’s prudent to pass over, for now, how the “Cancel Culture” should treat this question. Another day perhaps.)

After the defeat of the South, new, less favorable treaties, were signed with the Tribes. They were required to free their slaves and allow them to become tribal citizens. Each of the treaties stated that the Tribes had “ignored their allegiance to the United States” and “unsettled the existing treaty relations,” thereby rendering themselves “liable to forfeit” all “benefits and advantages enjoyed by them” including their lands.

This was an especially important historical fact to Chief Justice Roberts and the other justices in the minority. However, it wasn’t enough to forge the divide on the Court.

The concluding paragraphs from both opinions succinctly summarize their position.

Chief Justice Roberts concluded the minority opinion by stating, “As the Creek, the State of Oklahoma, the United States, and our judicial predecessors have long agreed, Congress disestablished any Creek reservation more than 100 years ago. Oklahoma therefore had jurisdiction to prosecute McGirt.”

Justice Gorsuch for the majority writes, “Congress has never withdrawn the promised reservation. . . If Congress wishes to withdraw its promises it must say so. Unlawful acts, performed long enough and with sufficient vigor, are never enough to amend the law. To hold otherwise would be to elevate the most brazen and longstanding injustices over the law, both rewarding wrong and failing those in the right.”

Yep. A deal’s a deal.