Impeachment Chronicles – Part III

I admit to being somewhat mystified.

My goal in writing these posts is to make the Constitution understandable to the citizens to whom it belongs. However, even for someone steeped in the more intricate elegance of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, the events of the last couple of weeks have been, — well, I really can’t find another word for it, — weird.

So rather than taking my usual Eagle’s eye view, I decided to focus on a few basic aspects of the Constitution in the context of what’s been going on in Washington. Keep at ground level so to speak. It always pays rich dividends to go back to the original language.

Events in the House of Representatives.

Article I, Section I of the Constitution states: “The House of Representatives shall choose their Speaker and other Officers: and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment.”

Okay so far

Article II, section 4 specifies the grounds for impeachment:

“The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.”

Two elements here. The removal from office can only be made after two events occur. First, an impeachment and Second, Conviction of the specific offenses.

That’s it. There are no other procedures. And there are no other grounds. Those three. Nothing else.

First as to grounds, some commentators, relying on Hamilton’s explanation in the Federalist Papers of high crimes and misdemeanors as addressing “the misconduct of public men . . . from the abuse or violation of some public trust,” contend no crime is required. That, however, is not what the Constitution says and is not what Hamilton said. The historical context of the phrase “high crimes and misdemeanors” makes it clear there has to be a crime, and it must be a crime committed against the State.

The other two grounds for impeachment are Treason and Bribery. There was some talk about those. Even by the so-called expert Constitutional law professors testifying before the Judiciary committee. However, the case was too weak and no allegation of either was included in the Articles of Impeachment passed by the House.

Another aspect to impeachment provision, which we ignore at our peril, is its applicability to other civil officers. This includes federal judges, including members of the Supreme Court. More on that later.

The Actual Articles of Impeachment passed by the House (after a mind-numbing day of inane commentary doled out in precious guarded minutes to the members of the House) are first, “Abuse of Power” and second, “Obstruction of Congress.”

The Articles failed to allege any of the Constitutional grounds for impeachment.

An ironic consequence of not adopting Articles which are based on actual grounds specified in the Constitution is that it theoretically invites a constitutional crisis the Majority party say they fear though never very convincingly. There may be an actual threat here.

Hypothetically if, in fact there was a conviction in the Senate, it would, on its face, be Unconstitutional. For the millions of supporters of the President it would be illegitimate. As the only remedy is removal from office, what if the President said No?

It’s the difference between the legal authority to do something and the actual raw power to do something. It’s a distinction not well understood by many of those in Congress who have no experience in what it is like to project power as opposed to just endlessly talking about it. For the vast majority of citizens, it’s one thing to be convicted after a legitimate trial. The expectation is the average citizen says, “well, I don’t like it, but he had his day in Court and he lost. Time to move on.” It’s quite another for them to be faced with the indisputable notion that the conviction is tainted and fraudulent.

There is also a problem with Vagueness. What do the terms Abuse of Power mean? What does Obstruction of Congress mean?

A little know aspect of Due Process is known and used by law students and lawyers when challenging a law or a regulation. It is the Void for Vagueness doctrine. It seems like the simplest concept in the world. A person charged with an offense must have knowledge of the what constitutes violating the law beforehand. If it is too vague to understand how are they know how to conform their conduct to the requirements of the Law? When a charge or offense is Void for Vagueness it is unconstitutional.

There has been a significant amount of discussion concerning rules and precedents within each chamber. i.e. what was done in the past, what were the rules used before?

Article I, Section 5 of the Constitution states “Each House may determine the Rules of its Proceedings, punish its members for disorderly Behavior, and with the Concurrence of two thirds, expel a Member.”

That means the House and Senate get to make their own rules and Courts have no power, no authority to intervene if they are unfairly applied. Simply because a rule says something or there was some parliamentarian precedent doesn’t mean the rule can’t be changed by the majority. The only restraint on the rules is Comity. A high-sounding word mostly observed out of fear that what you do to the minority party will be, someday, done to you if you lose the majority.

One of the Congressmen did make a point that stuck home with me. As many have said and as I warned in my last post there is a real danger if impeachments become a routine political tool used to remove a President whom a majority in the Congress object to. But is there a further danger?

This Congressman compared the danger of routine impeachments to what has happened to Senate Confirmation battles over appointments to the Supreme court. Before Ted Kennedy led a brutal assault against Justice Bork (see previous posts) confirmation hearings were formal, and dignified affairs. Since then they have devolved to scurrilous and baseless character assassinations as was done to Justice Thomas and Kavanaugh. Are we on the verge of seeing a similar development as to Presidents and will that lead to using the same tool being against other civil officers such as sitting federal judges including Justices of the Supreme Court?

And what’s more the Court’s don’t get to interfere. Other than the Chief Justice presiding, the courts can’t influence impeachment proceedings. In the case of Nixon (the judge not the President) vs. U.S. decided in 1993 it was held that whether the Senate had properly tried the impeachment of a federal judge was not judicially reviewable. Fair or unfair, the courts could not stop it.

On to The Senate

Article I, Section 3 states: “The Senate shall the sole Power to try all Impeachments. When sitting for that Purpose, they shall be on Oath or Affirmation. When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside: And no Person shall be convicted without the Concurrence of two thirds of the Members present.

Judgement in cases of Impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United State: but the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgement and Punishment, according to law.”

Two things here. Nothing says the Senate has to try an Impeachment. Having sole power means the ability to proceed as desired or not at all. And there is nothing requiring a physical transfer of the Articles nor any rule requiring the Senate to hear from the House at all. As to an oath: one is required, but it is not defined.

The maneuver taken by the House majority in holding back the Articles reminded me of my days as a District Attorney when a high-profile crime received a great deal of press attention. There were always a few a Police Chiefs and even a Sheriff’s captain or two who sought to shift responsibility for the case to my office before they did necessary and sometimes difficult investigation which was required to actually prove the case. Their assumption was that the political pressure of doing an arrest would require us to file the case before it was ready to be filed. They recklessly wagered I would not want to face the public fall out by seeing the arrestee released by refusing to file the case before the evidence was nailed down.

They learned different. I considered it a cheap trick and I told them so to their face and showed them I knew how to surf the political winds of making difficult intensely scrutinized decisions as well as they. They learned not to short circuit their investigations and to do their job before they submitted a case.

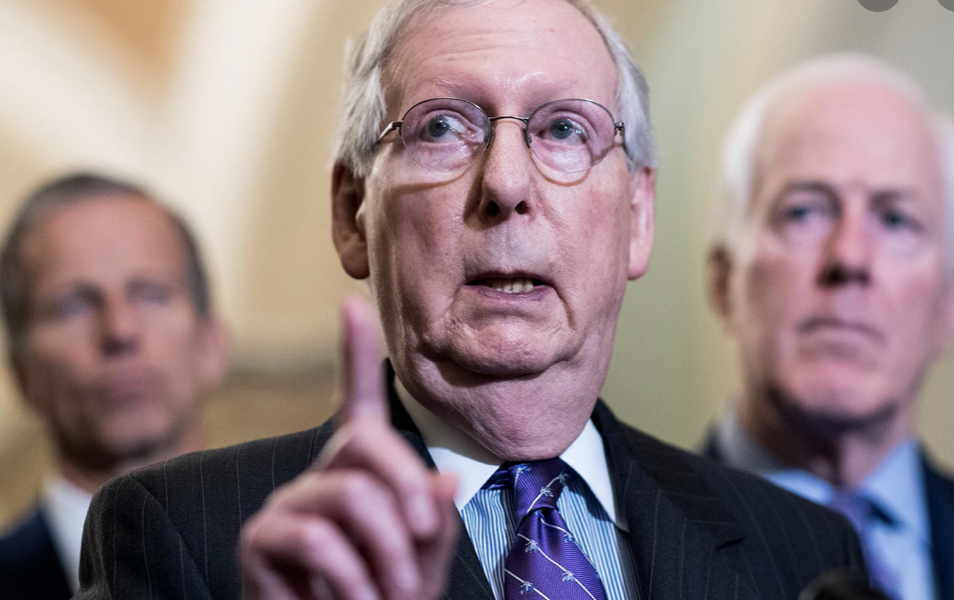

It seems that the Majority didn’t learn that lesson. They rushed their investigation, got a little cute with their charges and then thought they could use the case as leverage to require another entity to do their work for them. And take responsibility for it. I don’t know if Leader McConnell will fall for it or if his razor thin majority will hold. It’s easy to talk about but facing down a hostile press and taking the long view in a critical political situation isn’t easy. I had absolute control as a chief executive of a department with plenary power. McConnell’s situation is more nuanced.

But he’s a wily old fox.

Good luck.