Farmersville Tales – Part 8 – Nickel’s (episode two) – The Line

During my high school years there was a labor dispute at the store. The store was union, but negotiations on a new contract between the union (Retail Clerks #1288) and the owners of the store chain floundered. There was a strike. It lasted for many months.

Even though, as a student, I only worked weekends and summers, I went out on strike with the rest of the clerks. As a family, we were union people. My father, by then a member of the Operating Engineers, a construction union, undoubtedly influenced by his experiences with poverty, was adamant unions were a necessary means to secure adequate wages and benefits.

Because I was part time worker, the pay from the union strike fund (about $72 a week) was adequate for me. However, some of the clerks, like my brother, newly married with children on the way could not survive on such a paltry wage. As the strike dragged on without resolution, they were forced to leave to take other jobs. Those times were tough. But sometimes that can be a blessing. Forced to change careers, he went on to become a very successful businessman and investor.

There was a fair amount of animosity during the strike because people we had known all our lives, crossed the picket line and took our jobs. Though later, after the strike, friendships were reestablished, the animosity never completely dissipated.

Neither was it an entirely peaceful strike. Cars were vandalized, nails and tacks thrown on the parking lot and in the driveways. Of the four stores in the chain, (Farmersville, Exeter, Woodlake, and Tulare) the one in Tulare, burned down. Though a connection to the Strike was never established, there were suspicions.

And there were physical threats toward us. Mostly shouted from a safe distance. However, once, another teenager, a part time worker like me, and I were sent to the Woodlake store to man the picket line. The older guys wanted to stay closer to home and sent us, a couple of high school kids, out to the hinterlands. And probably because we were just teenage boys, we ended up being accosted by two carloads of toughs, cursing us and waving clubs and baseball bats. We locked ourselves in my friend’s car and they surrounded and smashed it up pretty good. Once they left, I ran to a pay phone and called the guys walking the line in Farmersville.

Within minutes they showed up and the picket line was manned again though this time with a group of men carrying weapons, including shotguns.

We saw the cars with the toughs come driving down the street toward us, but when they saw the reinforcements (and no doubt the weapons), they turned down a side street and never returned to harass us again.

The nature of Nickel’s as a crossroads changed during the strike and, in turn, Farmersville changed. As a busy bustling place along the highway, a place for the new arrivals to mix in, a place where we all felt the commonality of experience and a history that bound us as a people together, it all seemed to fracture. There was now less WE, more “US/THEM.”

After the Strike ended and a new contract was signed, most of the strikers returned to their jobs, and everyone buckled down determined to return things to the way they were, to build back the relationships between the workers and the customers, but, sadly, it wasn’t the same, could never be the same. A line had been drawn and its shadow remained.

It was while I was walking the picket line in Farmersville one Saturday that I met Cesar Chavez.

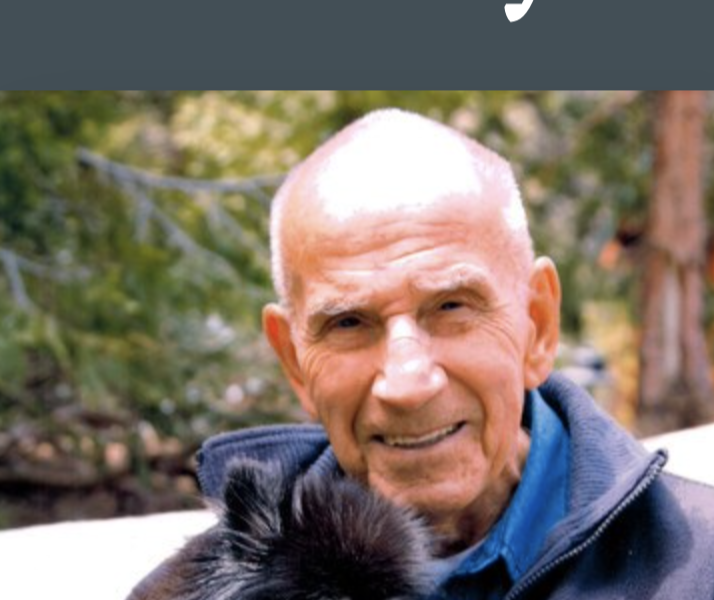

He was marching through town with a contingent from the United Farm Workers Union who were organizing in the fields down by Delano. It was a brief encounter, though I managed to have my picture taken with him.

Small in physical stature, I recall there was a calmness about him. He was certainly no screamer. Unlike the labor leaders of today, there was no shouting, no casting angry glares in every direction. He spoke in low respectful tones. But one listened. There was even a little laughter during the visit as some of the marchers tried to teach us Okies how to pronounce the word, “Huelga.”

Being just a kid on a picket line, I gave no thought to the politics of the situation. In later years that changed.

A couple of months later, out there on the picket line, my ambition to be a lawyer was born.

There were irregular visits to the picket line by union business agents. One was a big blonde headed man, big bellied, huge arms, feet. And no one to mess with. Not in those days. He had been a teamster organizer, once worked for the garment workers union in New York City and was loud, tough, and mean. When he showed up at the picket line to check on things, he would stomp down the line, cracking jokes, grabbing the door handles to the store, and shaking them so hard the glass windows rattled as if they would shatter. He took obvious delight in how he scared the clerks and customers inside the store who looked away and, prudently, never complained.

On one of his visits, he brought along a union attorney. Unlike the business agent, this man was smooth, nothing out of place. He too radiated a toughness, but not the thug like toughness of the business agent. Just extreme confidence.

His suit was expensive and immaculate. He wore a white shirt, obviously not from J.C. Penneys (like all mine,) and a bright silk tie. I remember watching him closely. Wherever he moved, he was the center. When he spoke, no one else did. There was a subtle nodding of heads among the men on the line, not signifying agreement, just because no one dared contradict what he was saying.

From the edges of the circle of men around him, I listened in as he spoke and it was as if, had his words been written down, there would have been no commas. He was one of those rare individuals who, because they have unquestioned confidence in what they are going to say, speak unhurriedly and in complete sentences. I thought to myself this is what I want to be. A lawyer, an attorney, who could go anywhere, speak to anyone about important matters and have that kind of deference and respect.

It was in my mind from then on to be a “Labor Lawyer” like him. By the time I completed law school, it didn’t matter if I represented Management or Union. It was being a lawyer that counted.

In careers, however, there is seldom a straight line from ambition to achievement. Once admitted to the Bar, I sought a job back home where I could gain experience in court. But then I got a taste of trial work, trying murder cases, lots of murder cases, loving it when I found the right dramatic moment to point my finger in a killer’s face and call him (or her) out for what they had done and what they were. I felt I had found my calling. I could have kept doing that forever, but after seven years of murder case after murder case, a rare opportunity opened. And along with the opportunity came the siren call of politics. But that’s another story for another day. Anyway, my dreams of being a “Labor Lawyer” were permanently shelved.

Many of our generation of Farmersville boys and girls, all of us once removed from the great migration West, encountered men and women who inspired them. Maybe an accountant, a physician, a master mechanic for a construction company, a business owner, who maybe owned a hardware store or an auto shop, a teacher who spoke of far-off places and times, or a teacher who spoke of economic theory. Or, importantly for our generation, a staff sergeant or a lieutenant in the armed services who taught us about such things as a defined chain of command and unit cohesion.

Of such contacts are dreams born. Dreams of who one can become. What we did know was it wasn’t going to be given to us. Nobody cared about our zip code and the social-economic level of its inhabitants. Nobody cared. Neither did we.

This was America after all. It promised equality of opportunity. Not based on WHAT you were, but WHO you were. Who you made yourself out to be. Who you became. And the Farmersville kids, those young boys and girls, the ones who had lived in houses with no running water, wood plank floors, canvas roofs, went on to succeed, as business owners, contractors, medical professionals, educators.

Once the strike ended, I returned to work at the store. Over the subsequent years, it was always a place I could go and work an evening or a weekend to make extra money. The last few years in the Service I was stationed overseas and then at an Air Force Base in North Dakota. When it came time to muster out, I hoped to go back to school. I wrote the owner of the store, Leonard Whitney, and told him I wanted to start school again and would like a job.

Leonard Whitney (always Mr. Whitney to us) was a war hero, an honored veteran of WWII. To him it was important that I was a veteran. In the return mail, he wrote that whenever I was ready to go to work, walk in, get an apron, put it on and get out on the store’s floor and work. I had that kind of support from Mr. Whitney right up to my first job as an associate attorney. His home was in Woodlake, but the flagship of his business was in Farmersville. To me, he was one of those people I met in Farmersville, good people, with whom you could have a conflict, such as the Strike, yet their integrity, their sense of justice, their caring about others made differences in people’s lives anyway.

I met many men and women like that working at Nickel’s.

And, for us, the sons and daughters of dustbowl migrants forced off the land in Arkansas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Tennessee and other places in the South and across the Midwest, who were just then, coming of age, like Farmersville itself was coming of age, they made a difference.

Farmersville Tales is published Sundays.

For more writings by Phil Cline visit philcline.com or my FB page at PhilClinePage.

Note to readers, I never open or use the Messenger app. I do have an email account, philcline@yahoo.com, for those who wish to directly communicate with me regarding my writings.