Farmersville Tales-Part Seven

Nickel’s (episode one of two)

At age 11, I became employed. Sweeping the parking lot of Nickel’s Pay-Less Food Market, was not my first job. Like most kids from Farmersville, I had worked in the fields alongside my parents, grandparents, and siblings. Childcare in the modern sense didn’t exist. You went where your folks went and if that was to work in the fields then that’s where you went. I was too young to be much good to anyone. I certainly never showed any aptitude for the fine arts of raising and harvesting crops. Nothing romantic to me about memories of working in someone else’s fields. At least not to me. I didn’t like it and never wanted to do it.

A Grocery store, however, was something else again. My father’s advice to both his sons had been to find a job where you could wear a white shirt and tie, a job where you could work inside. Out of the weather. He spent his life working in the fields and on construction jobs. For him, success meant an inside job, inside away from the dirt and grease and cold and heat, the pain of having a hand or arm or shoulder burned or bruised in wrestling machinery.

My brother, five years older, landed just such a job at Nickel’s Pay Less. Inside a store. As a clerk. And then later, through his friendship with the store manager, he helped get me a job sweeping the parking lot in the pre-dawn hours. I can’t say I was appreciative. At the time it appeared to me to be a miserable thing to do to a little brother.

Twice a week, my mother would wake me at four a.m. and send me on my way. I would walk through the sleeping town still half asleep, with that slightly nauseated feeling you get from getting up too early. It was a lonely walk in the dark. The shadows, the sudden night sounds, dogs suddenly barking, a cat dashing from one dark place to another could be scary to a kid.

Along the street, a few lights would come on in a house here and there. Men had to get to work and that meant, for these men, being at the work site as the sun rose. They had no choice. Neither did I. I had to get to the parking lot, get out the big wide push brooms and metal trash cans and get the lot picked up and swept before six a.m. Soon enough, clerks would be arriving at the store to unload trucks queued up in the alley and butchers would enter Dingle’s meat market out back of the store to trim and prepare the displays of meat and poultry. Soon after, the store manager would be unlocking the front door as the first customers arrived.

I soon took on the added responsibility of managing the bottle room. I didn’t like that either. It was cramped, full of dust and spiders. I stumbled around sorting soda bottles returned to the store by customers or kids for the small change the store gave for their return.

Eventually, I was promoted. Surrendered the parking lot and bottle room to another unfortunate kid and made it inside the store. I now dressed in slacks, white shirt and snap on bow tie arriving at the decent hour of 9 a.m. to assume the duties of what we called a “Boxer,” loading up groceries in bags and boxes and taking them out to a customer’s car.

My first day inside the store I thought would be my last. That morning the flow of customers was slow and the store manager, Gene Nickel, sent me home. My mother looked askance when I walked in the door, like it was my fault. An hour later my brother called and said the store had gotten busy and Gene wanted me to come back to work. When I arrived, Gene walked by and with a wry sardonic smile that I would get to know very well over the years, asked me “Where have you been?” I could hear my brother laughing.

At our job, we ran. Not because we had to, not because it was expected, more because we were young, healthy, athletic, and it was fun to run, felt good to run. It was exhilarating to get the bags and boxes out to the customer’s car, load ‘em up and sprint back inside before the next family in line had their groceries checked through. We knew all the customers and we knew the cars they drove. They habitually handed us their car keys before they finished paying their bill and we took off with the groceries, loaded them up and tossed them the keys on the way back in the store.

Later I got promoted to checker, ringing up the purchases. We had big, loud cash registers then. No mindless clerks, boringly running an item over a scanner. “Ringing up” the amounts on a cash register, calling out the prices was what we did. It became something of an art form. There was a music to it.

Still being in school, I mostly worked weekends and vacations. And the store was usually busy during those times. You had to keep moving, and that too was okay. It made the time pass quickly, bringing an end to the shift so you could break free for the evening, play ball, go the movies, or drag around town with your friends.

I did like the people part of the job. It helped me get past shyness and learn to deal with people of all ages, backgrounds, and temperaments. And their money. Dealing with people and their money will teach you a lot about a person’s true nature.

The store was busiest when paydays came. We cashed everyone’s pay roll checks. Lots and lots of checks. The floor safe, right up front by the registers, under the big front windows, was, on pay days, stocked full of bundles of cash. We moved back and forth to the safe, in full view of everyone pulling out the bundles to take back to the register and count out the cash. Interestingly, as I look back, there was never any noticeable concern over robbers.

We knew well the people we cashed checks for. We seldom asked for any form of identification.

Life takes many unexpected turns. Cashing a particular person’s payroll check every week was one.

Years later as a young green deputy district attorney, I drew the duty of appearing at a parole hearing at Atascadero to oppose a prisoner’s parole. In reading the file as I prepared for the hearing, I was incensed at the crime. It had happened years before while I was away in the Service and involved the rape and murder of a 12-year-old girl. It happened one Christmas just outside Exeter.

I was haunted by the picture of the girl’s bike turned over by the side of the road after she had been dragged off. As the hearing was being called, I took my seat at counsel’s table in the hearing room. When the side door opened and the convict was escorted in, I looked up. I sat there shocked. I knew the person. Oscar Clifton. I had routinely cashed his checks at the store. All those times he came in the store, he had appeared to be just a regular working guy.

The Store was a crossroads for Farmersville. Everyone who lived in Farmersville, or the areas outlying like Linnell Camp, Outside Creek, Cameron Creek, came to the store on a regular basis. Many of the people traveling through Farmersville from Visalia to Exeter and back the other way, also stopped at the store.

The people just passing through town on their way to somewhere else, provided another of life’s turns. One day, I saw a very pretty girl getting out of a car with some other girls and walking toward the front door. Farmersville had many pretty girls, but there was something different about this one. My older brother, noticing me giving her a good “lookin’ over,” asked me if I knew who she was. I shook my head. He said, “that’s’ Miss Tulare County.”

Many years later, in another of life’s turns, I became well acquainted and friends with her brother who was a well-known and respected lawyer in Visalia. He and I opposed each other on some very important cases. Though I made discreet inquiries about her whatever became of her, I never told him about that day.

Being the crossroads it was, Nickel’s was also the place that new arrivals to Farmersville came to shop. The inward migration from, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Tennessee and Mississippi, and related environs, continued, but had abated to a trickle by that time. The economic system that drove the migration from those areas had recovered from its sickness. The last of the arrivals from back there were, to us, just a bit more backward, just a might more ignorant than we, maybe came from a little further back in the hills and hollers of Appalachia. Nevertheless, they had still trekked the same path West we had taken only a generation earlier.

These latest arrivals pushed their carts down the isles of Nickel’s Pay Less, selected their groceries, milk, eggs, melons, and moved toward the front of the store to pay their bill with the wages they had earned working in the fields.

In those fields they were now working alongside a new generation of migrants arriving on different roads, from different places, coming to Farmersville, like us, in search of an opportunity for a better life.

Next week, in Nickel’s-episode two, I’ll tell you about “Labor Strife at the Store” and the day I shook hands with Cesar Chavez in the parking lot of Nickel’s Pay Less.

Farmersville Tales is published Sundays.

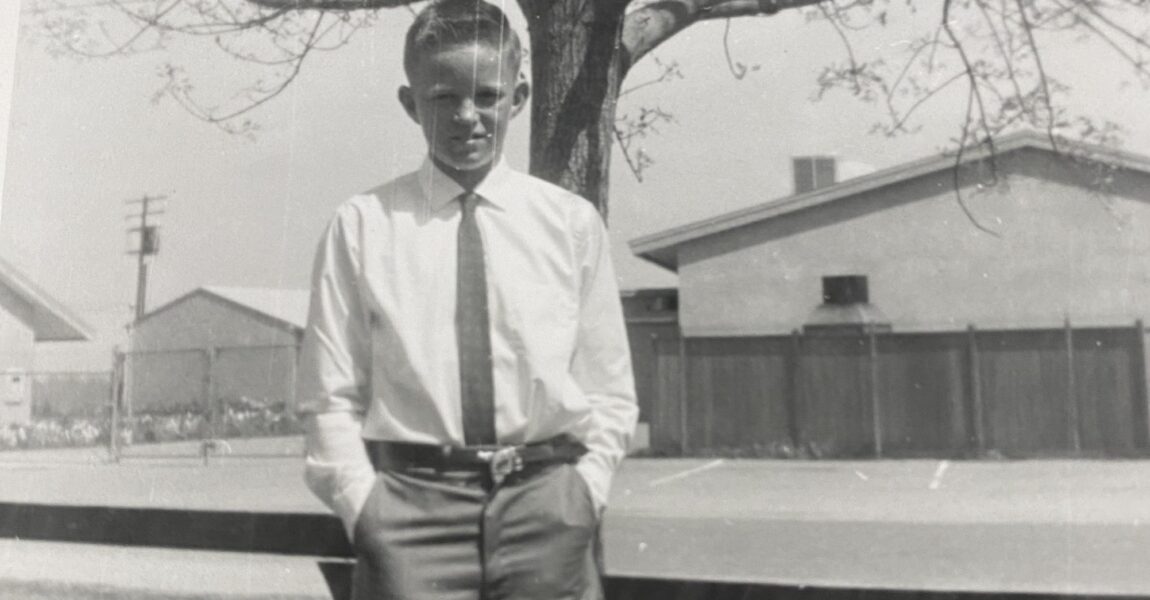

The photos are of a handsome young box boy, ready to work.

For more writings visit philcline.com or my FB page @PhilClinePage.

Note to readers: I do not open or use the app, “Messenger”. I do have an email account dedicated to matters concerning my writing. It is [email protected]